Τhe Project

Kastritsa

BACKGROUND OF PREVIOUS RESEARCH

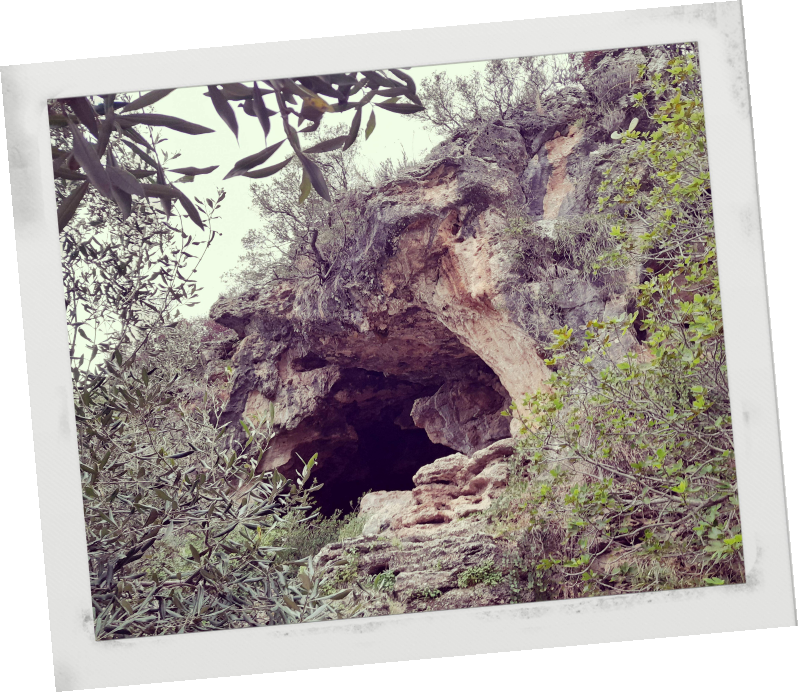

The rockshelter of Kastritsa is located about 10 km southeast of Ioannina city and close to the shores of Lake Pamvotis. It was identified as a prehistoric site and excavated by a team of British archaeologists led by Eric Higgs in the years 1966 and 1967, under the auspices of Cambridge University and the British School at Athens. The excavations yielded a large collection of Upper Paleolithic cultural remains, including stone and bone tools, as well as abundant habitation features (hearths, post-holes and ‘chipping floors’). The archaeological sequence of Kastritsa was revisited in the 1980’s by a team led by Geoff Bailey. This reappraisal opened the way for a series of PhD theses, which focused on aspects of the stone-tool industries (Adam, 1989; Elefanti, 2003), the faunal assemblages (Kotjabopoulou, 2001) and the characteristics of site use (Galanidou, 1997). A series of radiocarbon dates published in the beginning of the 1980’s and 2000’s chronologically place the occupation of Kastritsa well within the late and final Gravettian period. It is assumed that the site periodically served as a base camp or transit camp, likely as part of a broader network of sites in the cultural landscape of the Epirote mainland. In order for them to cover their dietary and everyday needs, the hunter-gatherers at Kastritsa made use of the rich faunal and floral communities of the lakeshore flatlands, but also the neighboring mountainous areas.

Grava Cave

BACKGROUND OF PREVIOUS RESEARCH

The cave of Grava is located in south-west Corfu, on the southern slopes of the mountain of Ayios Mathaios and close to the Byzantine site of Gardiki. The site lies at an altitude of about 60 m. from which the coast is visible. It was discovered and excavated in the late 1960’s by the Greek archaeologist Augustus Sordinas. The excavation yielded around 2000 lithic artifacts, as well as faunal remains, that were collectively attributed to the terminal Palaeolithic (“Romanellian”, Late Epigravettian). The finds included also one personal ornament, in the form of a perforated deer tooth. Sordinas’ brief reports on the site and the finds were not followed by any more systematic study and publication of the material, and the excavation was not re-visited in the following years.

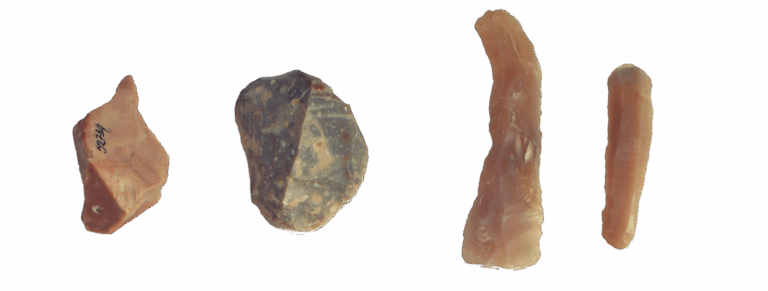

Lithic analysis

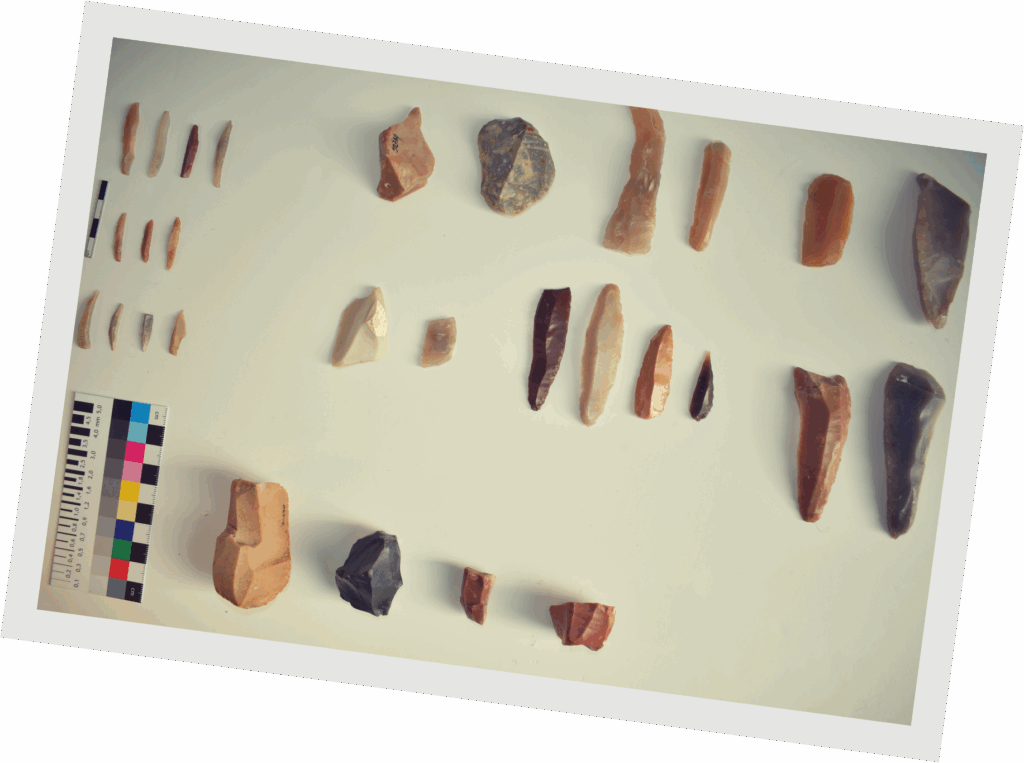

Previous techno-typological analysis of the Kastritsa lithic material (Adam 1989), identified a chrono-stratigraphic differentiation in the technology and the tool inventory between the uppermost stratigraphic unit (stratum 1), of Epigravettian character, and the lower ones (strata 3-8), while the lowermost unit (stratum 9) indicates a more erratic and limited use of the site (Adam 1989; Galanidou, 1997). The material from the remaining levels, namely strata 7, 5 and 3 –and mostly 5 and 3– display technological characteristics that call for a re-evaluation, to assess whether these assemblages can be securely attributed to the (late?) Gravettian.

The lithic industry from Grava has not been fully published, except for preliminary and short reports (Sordinas 1969, 1970). A preliminary analysis of the stone-tool industry by E. Adam showed that the material exhibits technological and typological characteristics similar to the assemblages from strata 3 and 1 of Kastritsa (Adam 1996, 2007), suggesting a possible technological/chronological linkage between the two assemblages. However, this hypothesis has not been yet evaluated, and the site was never dated by means of radiometric dating.

The possibility that the Kastritsa lithic and organic artefact assemblages, as well as (part of?) the Grava material, should be attributed to the (late) Gravettian has remained untested. The GRAVETTIAN research program is testing this hypothesis, with the aim to provide an updated appraisal on the cultural attribution of the studied assemblages.

Lithic industries from this period from Italy and the Balkans are sometimes called “Gravettoid”, which itself reflects the regional character and the problematic aspects in comparing those materials with their chrono-cultural equivalents from the rest of Europe. Nevertheless, such assemblages are thought to confirm the autonomous formation of Gravettian centers in these areas (Kozłowski, 2015). Macroscopic, technological and typological criteria will guide comparisons of the studied lithics from Kastritsa and Grava with published records from other sites in Greece, the Mediterranean (particularly Italy) and the Balkans.

Bone artifact study

The Gravettian is characterized by an unprecedented use of animal osseous materials (bone, antler, teeth, ivory) for the production of tools or hunting gear, in parallel with a proliferation of symbolic objects manufactured also from organic materials. Consequently, the osseous artefacts component is a crucial parameter for the re-visit and investigation of the targeted Upper Palaeolithic sites in Epirus and Corfu.

At Kastritsa, most of the identified organic artefacts come from the extensive anthropogenic deposits of the middle and upper part of the stratigraphic sequence. The assemblage includes mainly points, awls, spatulae, as well as a few needle fragments and manufacturing waste indicating in situ production, made from antler and mammal long bones. A thorough study of the morphological and technological traits of these artefacts will expand our criteria for comparisons with published Gravettian organic industries, contemporary to those of Kastritsa. The primary goals of the study of the organic artefacts are: 1) to determine technological and behavioral trends comparing the industry from Kastritsa to those from contemporary contexts with a Gravettian component, and 2) to explore the role of local natural, economic, and cultural backgrounds to the shaping of the typological and technological profiles of these industries. To this end, we shall combine the study of the sources of the bones used to make the artefacts, the morphometric characteristics of the latter, and the manufacturing and use wear marks preserved on their surface with available palaeoenvironmental, subsistence, spatial, and taphonomic data.